Background

The vitality of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary depends on a healthy and dynamic balance between ocean water and fresh water. Over the past several decades, however, larger and larger quantities of fresh water have been diverted for human use from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River watershed, which drains into the Estuary. As a result, this balance has been lost, with devastating impacts to the ecosystem and to certain segments of the economy. Increasing and improving the timing of freshwater flows through the Bay-Delta is essential to restoring the health of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary.

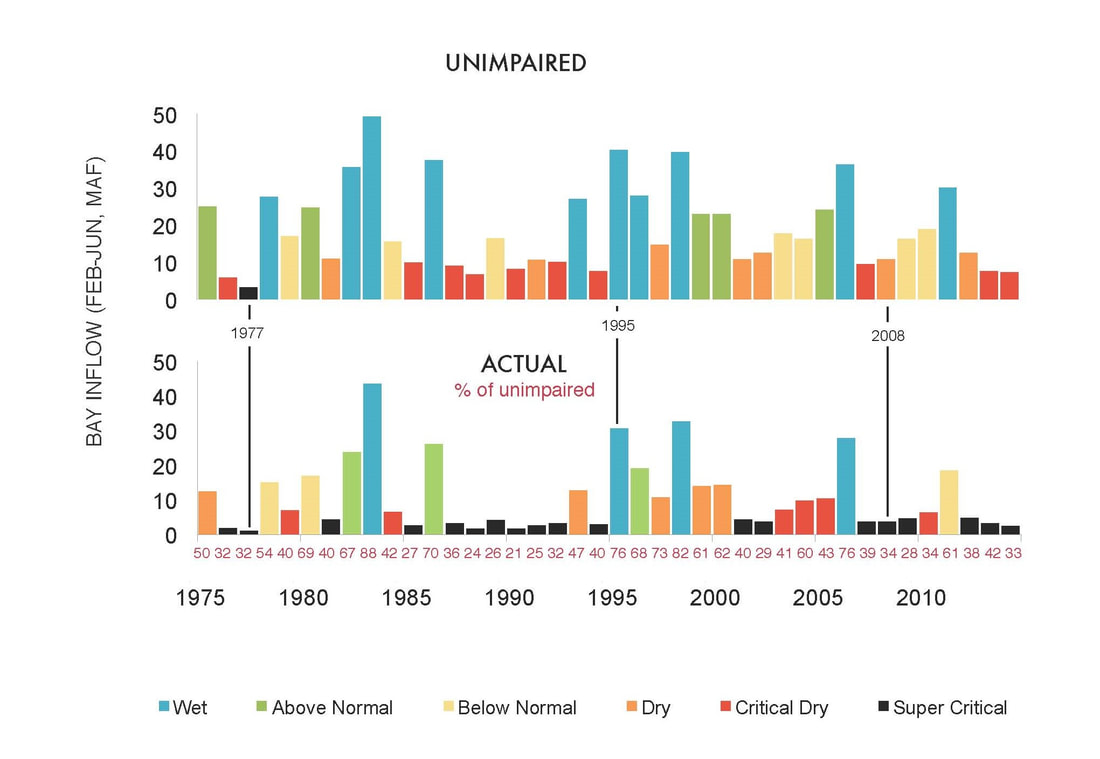

For the past decade and more, the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary has been in a state of chronic drought (Figure 1).

For the past decade and more, the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary has been in a state of chronic drought (Figure 1).

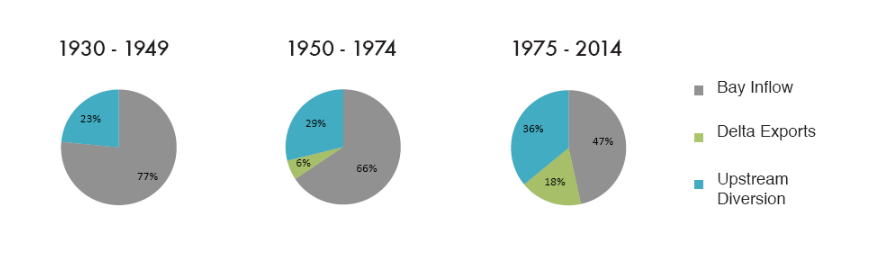

Increasing amounts of fresh water are being captured behind dams and in reservoirs and diverted by pumps, canals and pipes before ever reaching the Bay, “impairing” natural conditions (Figure 2). In fact, despite the critical need for adequate flows, less than half of the freshwater that drains into the Bay-Delta system has reached the Bay in recent years.

Despite millions of dollars invested to clean up the Bay and restore habitat, none of the Bay fish communities in any part of the Bay-Delta system have improved in the past 20 years. Instead, 6 native fish species that rely on the Bay’s mix of fresh and salt water have been listed under the federal and/or state Endangered Species Act. Fish species are declining rapidly, including commercially important and endangered species such as salmon, sturgeon, smelt, and several species of sport fish. If action is not taken, this decline will have mounting impacts on the health of the Bay and Delta—not just fish species, but the entire system.