|

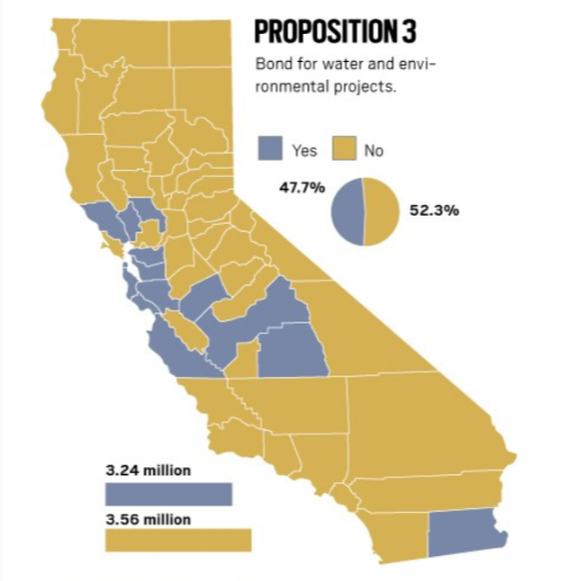

Voters rejected Proposition 3, “Californians for Safe Drinking Water and a Clean and Reliable Water Supply,” at the ballot box on Wednesday. The $8.8 billion general obligation bond would have provided $200 million to restore San Francisco Bay wetlands, funded clean, safe drinking water in the Central Valley, and helped to extend water supplies through wastewater recycling, urban and ag conservation projects. It seemed to have something for everyone, so why didn't it pass? A few thoughts: - Distaste for "pay to play": Voters didn’t like the earmarked funds for specific improvements that would benefit the business groups who financed the bill. Although proponents asserted that every part of the state would benefit from the bond, over $1.2 billion of the bond was dedicated to funding improvements in 4 specific regions: San Joaquin Valley between Fresno and Bakerfield, San Francisco Bay, Oroville Dam, and Napa and Solano counties. And, in fact these areas were some of the only counties where the proposition passed (see www.mercurynews.com/2018/11/08/election-2018-heres-how-california-counties-voted-in-the-midterms/). - Water Bond fatigue: the third related general obligation bond in 5 years; voters may have grown tired, for now, of feeling like they were throwing money at the problem. And with memories of the recent historic drought fading, the issue took a back seat to the many other measures on the ballot, including homelessness and highways. - Too ambitious: even Prop. 1, which passed in 2014 after eight years without a water bond, was only $7.5 billion. The sizeable price tag may have put off voters, particularly on top of the other points above. What’s next?

If California sinks back into drought, voter interest could be piqued once again. But it will probably take a few years before voters are ready for another water bond. A measure introduced by the Legislature with fewer specific earmarks could receive a more favorable response if the timing is right. California needs to invest substantial funds into water infrastructure improvements to improve drinking water quality, restore habitat, and develop alternative water supply sources like rainwater capture and advanced treatment. These needs cannot be resolved entirely at the local level, so at some point there will be another water bond on the ballot.

0 Comments

Earlier this month I visited Reclamation District 108 in the Colusa Basin, which straddles the boundary between Yolo County and Colusa County on the west side of the Sacramento River. I went at the invitation of Lewis Bair, General Manager of RD 108, after we sat together as panelists with opposing views at the recent California Water Policy Conference.

The premise of the panel was a debate on the merits of a functional flow management approach vs. an unimpaired flow management approach, and I was the sole proponent of the unimpaired flow approach (sitting in for Barbara Barrigan-Parrilla of Restore the Delta). During the panel, I made reference to the benefits that farmed land provides to downstream water users, in contrast to urbanized lands, using an example from New York. Mr. Bair correctly recognized this as ignorance of more local examples and offered to show me some of the habitat restoration efforts his district has been undertaking. When I pulled up to the River Garden Farms office near the banks of the Sacramento River, I was met by Mr. Bair, Todd Manley, Director of Government Relations for the Northern California Water Association (NCWA), and Roger Cornwell, General Manager of River Garden Farms. They had put together a PowerPoint and a personalized packet to provide me with an overview of their projects. It’s a good thing they had, too, because there were a lot of projects to digest. The first thing we did was talk about River Garden Farms’ experimental rootwad project on the upper mainstem Sacramento River. We couldn’t visit it, since the project is 190 miles upstream, in Redding. In Redding, nowhere near River Garden Farms’ land along the Sacramento River. Why is a farmer in Yolo County funding a fish habitat project four counties away, to the tune of $400,000? And Roger didn’t just fund the project, he led it through multiple permitting hurdles and obtained specialized construction equipment to install the 12,000 pound limestone boulders with large tree trunks and rootwads bolted to them. The project area just downstream of Shasta Dam provides deep, cold water habitat, but lacks structural complexity instream to provide juvenile salmon with rearing habitat and refugia from predators. The installation of these large structures at depths of 12-20 feet was an experiment to see if the juveniles would use large woody debris in deeper water; initial underwater monitoring has yielded very positive results:

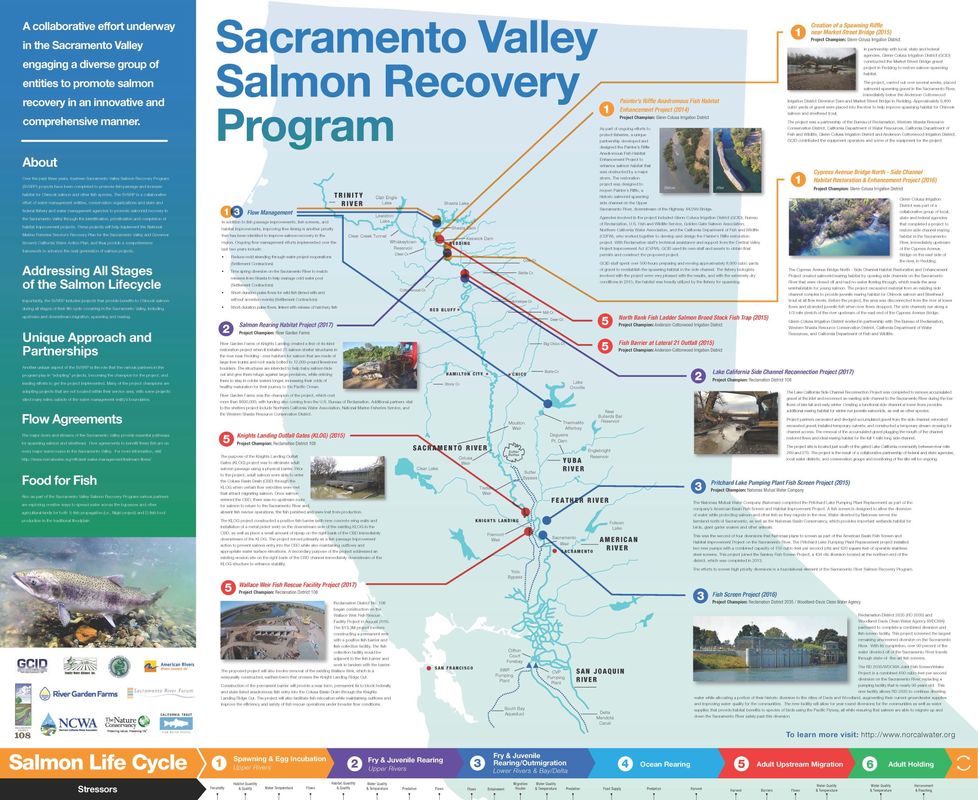

This is only one of a suite of projects to enhance Sacramento River salmonids at every stage of the life cycle through the Sacramento Valley Salmon Recovery Program, and farmers like Roger in RD 108 and NCWA are championing these projects. During our short morning together, Lewis, Roger, and Todd talked about the rootwad experiment, an extensive series of fish screen installations, an experiment in revised winter flooding management practices on rice fields to grow biomass or “floating fillets” for salmon, an 116-acre floodplain habitat restoration project, and two multi-million dollar positive fish barriers designed to prevent fish from straying into the dead-end channels of the Colusa Basin Drain. Their enthusiasm for these projects was palpable.

One of the main motivations for them to do this work, of course, is to maintain their water supply. Lewis was very forthright in stating that they hope to recover salmon populations through habitat restoration and fish passage improvements rather than through reduced diversions. Lewis said, as we stood on the levee along the Sacramento River, “Let’s try these actions first, and if they don’t work, then let’s look at what we have to do with flows.”

They put their money where their mouths are, as the saying goes. The Wallace Weir Fish Rescue Facility and fish passage improvement cost $13.3 million and was designed, permitted, and constructed in just over two years. Originally an earthen berm installed to create an irrigation backwater, the temporary weir has also served an essential function by blocking fish passage into the dead-end Colusa Basin Drain. Unfortunately it fails during flood events. The re-design and reconstruction of the Wallace Weir incorporates a fish rescue facility and an inflatable dam, and will help control water releases for both fish and irrigation needs.

The pace and scale of implementation of these projects is mind-boggling, with immediate benefits to salmon in many cases. Not a single advocate for improved freshwater flows will make the argument that you can improve instream flow management without habitat restoration. But much of the conventional wisdom holds that a change in water management can take place much faster than a habitat restoration project. Permitting alone can take years, and riparian restoration projects can take longer than a decade to develop substantial canopy cover. Comparatively, these projects—more than 14 of them, according to the poster above and additional ones shared with me during my visit—have all been implemented in five years.

These successes show what a group of farmers can do, with the assistance of scientific experts and with substantial funding that comes out-of-pocket in many cases. Why do they do it? While the obvious motivation may be to protect their water supply, the less obvious motivation—for urban dwellers less connected to the land on which they live—is that it’s part of their stewardship ethic for the land they farm. These are people just as passionate about the mayflies they are producing for salmon rearing as they are about the processing tomatoes, rice, and sunflowers they are growing for human consumption.

Lewis Bair remains hopeful that water users of all stripes can come together on solutions that will enable fishes and farms to thrive. He says, "I don't want to retire and say we did nothing" to improve conditions for endangered species. With folks like Lewis, Roger, and others leading the way, there is plenty of reason for hope. |

Details

AuthorsFriends staff, interns, and Board members. Archives

November 2018

Categories

|

|

© Friends of the San Francisco Estuary. All rights reserved.

Friends of the San Francisco Estuary is a 501(c)(3) organization Tax ID#: 68-0265026 Web Designer: Mark Bentivegna

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed