|

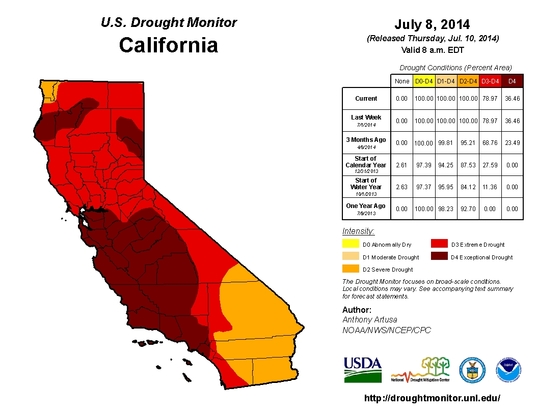

Author: Nicola Overstreet Governor Brown surveyed California’s North Coast and declared his sorrow over what he named “a major American disaster.” Intense rains all across Northern California had caused massive flooding, threatening homes, businesses, livestock, and lives. Del Norte, Mendocino, Siskiyou, Trinity, and Sonoma counties were hit especially hard, and in Humboldt County alone the flooding caused $100 million in damage. Governor Brown remarked that a flood of that magnitude could only happen “once in 1,000 years,” and it became known as the Thousand Year Flood. It was also known as the Christmas Flood of 1964. That was the landscape of California fifty years ago – Governor Pat Brown was declaring disaster areas in 34 counties, as rescue helicopters scoured floodwaters for survivors. Now, another Governor Brown has declared a very different kind of emergency in California. On January 17, 2014, it was not an excess of water, but an overwhelming lack, that pushed Governor Jerry Brown to declare a Drought State of Emergency. As of July 2014, the entire state is experiencing drought levels that are considered severe or worse, with 36.46% of California experiencing exceptional drought conditions. Junior water right holders have been ordered to stop diverting water from rivers. Discussions of groundwater regulation, mandatory conservation, water insecurity, and emergency drought relief dominate the discourse on water policy in California. It’s certainly no stretch to say that Northern California is facing a landscape in 2014 that is drastically different to that of 1964. But weather conditions are not the only thing that has changed in the Bay Area. In the 1960s, industrial facilities pumped their waste directly into the San Francisco Bay, and sewage entered the Bay in 83 places. Bay Area residents did not view the Bay as a state treasure, but as a dumping ground. That began to change in the 1960s with the efforts of organizations such as Save the Bay, and the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972. Now, fifty years later, 92% of bay area residents agree that a “clean, healthy and vibrant San Francisco Bay” is important for the region’s economy. And they’re right: tourism in the San Francisco Bay area generates over $8.93 billion/year, and fishing and farming communities along the Bay-Delta depend entirely on the health of the waterway. But more importantly, Bay Area residents now view the Bay as a crucial part of their own identities. Given the extent to which weather conditions and social attitudes towards the Bay-Delta have changed over the past 50 years, it would be ridiculous for any piece of legislature related to the water of the Bay-Delta to hold public policies static for 50 years. Wouldn’t it? The Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), a 50-year plan that aims to increase water reliability while restoring Delta habitat, is proposing exactly that. The project would consist of two tunnels, buried 150 feet beneath the heart of the Delta, which would help divert water from the Sacramento River to southern California. In order to proceed, the project planners must apply for permits from federal and state fish and wildlife agencies. The BDCP includes an adaptive management and monitoring program that accounts for reasonably anticipated ‘changed circumstances’ such as flooding, levee failure, drought, vandalism, or wildfire. ‘Unforeseen circumstances’ are those that the BDCP does not expect. These circumstances could affect one or more species, or the habitat, natural community, or geographic area covered in a permit. If the unforeseen circumstance involves ecological degradation resulting directly from the BDCP, the project operators will have to mitigate the situation. However, given how many factors influence the ecosystem, it’s unlikely that it can be proven that any one cause – BDCP included – is primarily at fault for environmental decline. For unforeseen circumstances, the permit holders will have regulatory assurance in the form of the ‘No Surprises’ rule. The rule maintains that once a permit has been issued, the federal government cannot require additional conservation or mitigation measures, or restrictions on resource use, to address unforeseen circumstances. As currently proposed, the BDCP is ultimately not flexible enough to meet the demands of the ever-changing environment in California, where “unforeseen circumstances” are the rule, not the exception. Cape Horn Dam in 1964 (left) and Scott Dam in 2014 (right) - Eel River, California In 1964, "Water over both Cape Horn and Scott Dams was so high that you could barely tell a dam was under the flow." (x) If Governor Pat Brown had been told that extraordinary water shortages would direct water policy conversations only twelve years after he stood looking out over the flooded North Coast, it would have been difficult to fathom. And yet from 1976 to 1977, rainfall in California was the lowest on record, and the resulting drought decimated California industry. The climate, ecosystems, and social perceptions of the Bay-Delta have changed dramatically over the past 50 years, and “no surprises” is not a promise that the BDCP make to Californians.

2 Comments

The Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), a $16--okay, maybe $24--no, wait it could be closer to $57--BILLION dollar plan to produce a more reliable water supply and recover endangered species, is the focus of much speculation, worry, and confusion. And for good reason: not only does the plan involve the construction of some of the largest water infrastructure California has ever seen at an estimated cost that already exceeds the Chunnel, but no one, not even the planners, is really sure that it will do what it promises. In fact, some folks are pretty sure it won't deliver on either of the two co-equal goals of reliability and recovery. So, understandably there are a fair number of questions surrounding BDCP, and the folks at BDCP have begun a blog to dispel certain "stubborn 'urban myths' that are being perpetuated." We found one of the myth corrections to be woefully inaccurate, and since the BDCP blog does not provide for public comments, we will debunk the debunking here. From the BDCP blog: Myth: The BDCP fails to analyze possible effects on San Francisco Bay. Fact: The BDCP does indeed analyze the effects of the project on San Francisco Bay and other water bodies downstream of the Delta. Analyses found that because there are no project diversions downstream of the Delta, the only effects of the project on the San Francisco Bay Area would be indirect and related to flow. According to the Department of Water Resources’ Delta Atlas, average tidal flow through the Golden Gate Bridge is 2,300,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) and average tidal flow at Chipps Island is 170,000 cfs. The maximum amount that BDCP would change flows downstream of the north Delta diversions is 9,000 cfs (and most of the time it would be much less). Therefore, at most, BDCP diversions represent only 5 percent of the flows at Chipps Island or less than 0.4 percent of tidal flows at the Golden Gate Bridge. Effects within San Francisco Bay would be within this range, diminishing greatly away from the Delta. Because these changes in flow are so small compared to the tidal range within the Bay, the plan concludes that there would be no effect of BDCP on the San Francisco Bay ecosystem or its native species. Okay, what does this really mean? Let's break this down: "Analyses found that because there are no project diversions downstream of the Delta, the only effects of the project on the San Francisco Bay Area would be indirect and related to flow." The effects of the project on San Francisco Bay are indirect because there will be no construction or habitat restoration activities taking place in the Bay. The indirect effects on San Francisco Bay have to do with BDCP making changes to the rate, timing, and amount of freshwater flow that will reach the Bay. The Bay is part of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary, a mixing zone of fresh and salt water. The Bay-Delta Estuary depends on two types of flow: tidal salt water flows from the Pacific Ocean and freshwater flows from Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and smaller tributaries. The ratio of fresh water to salt water in the Bay fluctuates depending on location, time of day, and climate patterns, but both are essential to a healthy, functioning system. "According to the Department of Water Resources’ Delta Atlas, average tidal flow through the Golden Gate Bridge is 2,300,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) and average tidal flow at Chipps Island is 170,000 cfs. The maximum amount that BDCP would change flows downstream of the north Delta diversions is 9,000 cfs (and most of the time it would be much less)." The statement above implies that 9,000 cfs of freshwater flow is insignificant compared to tidal flows of 2,300,000 cfs or 170,000 cfs. But this logic conflates freshwater flow with tidal flow. Tidal flows play a different role in shaping the Bay ecosystems than freshwater flows. Comparing freshwater flow to tidal flow is comparing apples to oranges. To understand the logic used by BDCP better, let's use a baking analogy provided by biologist Jon Rosenfield: We did study the effect of the baking powder in your muffin recipe, but since the mass of the powder was only a small fraction of the mass of the muffins produced and its effects were indirect, we concluded that the amount of baking powder in your recipe has no effect on the final muffin. If we want to compare apples to apples (or muffins to muffins), then we need to compare 9,000 cfs of freshwater flow to be taken by BDCP to total freshwater flow, not tidal flow. The Sacramento River, where the new facilities will be located and a significant source of the Bay's freshwater flow, had an average flow rate of 23,490 cfs during the period 1949-2009. So, to use the same kind of math that the BDCP blog uses, we should say that BDCP would actually be changing freshwater flows on the Sacramento River by 38%. 38% of the Sacramento River paints a very different picture of the impact of BDCP on San Francisco Bay when compared to the example offered by the BDCP blog. Of course, that's not the entire story. The Sacramento River can run at much higher and lower rates than the average, and the twin tunnels will have to operate under regulations that often will prevent the full diversion rate. Also, while the Sacramento River is the largest source of fresh water (median=85%) to the San Francisco Bay, there are other significant sources such as the San Joaquin River, in-Delta tributaries, and smaller Bay tributaries. Plus, there are many ways in which BDCP's changes to freshwater flows may affect the Bay not captured by this simple equation. Freshwater flows from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers play an essential role in providing the Bay with nutrients, diluting and dispersing pollutants, reducing water clarity (and thus possibly threats of toxic algae blooms), and lowering salinity for the wide range of fish, birds, and animals that use the Bay. The Bay Delta Conservation Plan owes the people and wildlife of San Francisco Bay more substantial evidence for the conclusion that this large project upstream will have no effect on our region than erroneous "myth" busting. |

Details

AuthorsFriends staff, interns, and Board members. Archives

November 2018

Categories

|

|

© Friends of the San Francisco Estuary. All rights reserved.

Friends of the San Francisco Estuary is a 501(c)(3) organization Tax ID#: 68-0265026 Web Designer: Mark Bentivegna

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed