|

Author: Nicola Overstreet The San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary is the largest estuary on the west coast of the Americas. It’s also one of the largest points of contention in California’s ongoing struggle to allocate its supply of water. Often, the debate over how much water should be siphoned off from the Bay-Delta and where that water should go is framed as a battle of “fish vs. farmers.” Farmers in the San Joaquin Valley – whose livelihoods depend on water from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers of the Bay-Delta– lament that the amount of water they can use is restricted, seemingly because of environmental regulations protecting Delta fish. When House speaker John Boehner visited Bakersfield in January this year, he remarked, “How you can favor a fish over people is something the people in my part of the world would not understand.” Farmers like Jose Ruiz have been quoted echoing the sentiment, saying that people who have qualms about taking water from the Delta are “worrying about the fish but not about the humans' life.” Those who tout the fish vs. farmers conflict as the root of California water issues appear to believe that the only thing preventing farmland from flourishing through the entirety of the Central Valley is a collection of heartless environmentalists. Some people have taken issue with the supposed clash between fish vs. farmers, because it ignores the many Californians who make a living off of fish both in the Delta and along California’s thousand mile coastline. George Skelton, a political columnist, writes that “it's not about farmers vs. fish. It's about farmers vs. fishermen. Or almonds vs. salmon.” However, reality is still not quite so simple. As it turns out, the group most overlooked by the fish vs. farmers dichotomy actually consists of more farmers. Farmers based along the Sacramento and within the Delta oppose the diversion of fresh water from the Delta because they too need it to maintain their way of life. In a healthy estuary, salt water flowing in from the ocean mixes with fresh water flowing in the opposite direction, stopping the salt water from advancing. However, as that fresh water is diverted away from the Delta, salt water can move further upstream from the Bay and into the Delta uninhibited. Residents of cities like Antioch worry about salt water creeping in from the Bay; their drinking water comes primarily from the Delta. Saltwater intrusion into the Delta affects the estuary ecosystem, drinking water quality, water recreation, and more. And it also scares people like Lynn Miller, whose family has farmed alongside the San Joaquin River for 113 years. As salt water enters the Delta, it will destroy their riverside farm. So maybe the dichotomy isn’t fish vs. farmers, but farmers vs. farmers. Or perhaps it’s closer to Delta farmers and residents and fisherman and boaters and environmentalists and some Bay Area residents vs. Central Valley farmers and residents and other Bay Area and Southern Californian residents. There are thousands of interest groups clamoring to get a hold of the Delta’s fresh water and “fish vs. farmers” oversimplifies and misrepresents the already confusing political discourse surrounding California water.

During times of crisis, people have a tendency to react with knee-jerk policy recommendations. One argument frequently made is that loosening environmental regulations will help to immediately alleviate the drought’s effects, which seems like sound reasoning when viewed through the lens of fish vs. farmers. If you sacrifice the fish, you may help the farmers. But in reality, environmental regulations don’t only protect the environment. They protect the communities that rely on the integrity of that environment. When environmental regulations on the San Francisco Estuary are relaxed or ignored, the fish do suffer, but so do recreational and commercial fisherman all along the coast and all of the communities of the Bay and Delta. By focusing on the interests of Delta fish and ignoring how connected those interests are to the needs of Bay-Delta residents, “fish vs. farmers” trivializes the importance of the well-being of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary. The false dichotomy of fish vs. farmers should have no place in serious California water policy conversations.

3 Comments

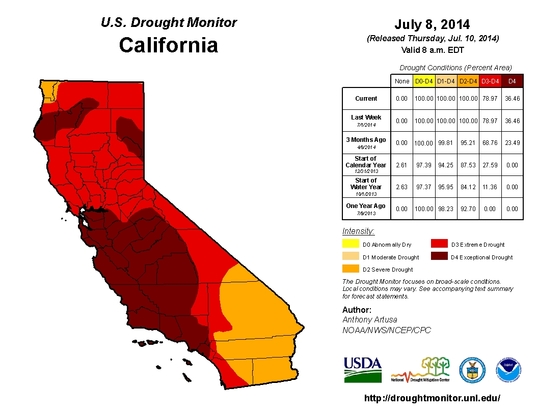

Author: Nicola Overstreet Governor Brown surveyed California’s North Coast and declared his sorrow over what he named “a major American disaster.” Intense rains all across Northern California had caused massive flooding, threatening homes, businesses, livestock, and lives. Del Norte, Mendocino, Siskiyou, Trinity, and Sonoma counties were hit especially hard, and in Humboldt County alone the flooding caused $100 million in damage. Governor Brown remarked that a flood of that magnitude could only happen “once in 1,000 years,” and it became known as the Thousand Year Flood. It was also known as the Christmas Flood of 1964. That was the landscape of California fifty years ago – Governor Pat Brown was declaring disaster areas in 34 counties, as rescue helicopters scoured floodwaters for survivors. Now, another Governor Brown has declared a very different kind of emergency in California. On January 17, 2014, it was not an excess of water, but an overwhelming lack, that pushed Governor Jerry Brown to declare a Drought State of Emergency. As of July 2014, the entire state is experiencing drought levels that are considered severe or worse, with 36.46% of California experiencing exceptional drought conditions. Junior water right holders have been ordered to stop diverting water from rivers. Discussions of groundwater regulation, mandatory conservation, water insecurity, and emergency drought relief dominate the discourse on water policy in California. It’s certainly no stretch to say that Northern California is facing a landscape in 2014 that is drastically different to that of 1964. But weather conditions are not the only thing that has changed in the Bay Area. In the 1960s, industrial facilities pumped their waste directly into the San Francisco Bay, and sewage entered the Bay in 83 places. Bay Area residents did not view the Bay as a state treasure, but as a dumping ground. That began to change in the 1960s with the efforts of organizations such as Save the Bay, and the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972. Now, fifty years later, 92% of bay area residents agree that a “clean, healthy and vibrant San Francisco Bay” is important for the region’s economy. And they’re right: tourism in the San Francisco Bay area generates over $8.93 billion/year, and fishing and farming communities along the Bay-Delta depend entirely on the health of the waterway. But more importantly, Bay Area residents now view the Bay as a crucial part of their own identities. Given the extent to which weather conditions and social attitudes towards the Bay-Delta have changed over the past 50 years, it would be ridiculous for any piece of legislature related to the water of the Bay-Delta to hold public policies static for 50 years. Wouldn’t it? The Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), a 50-year plan that aims to increase water reliability while restoring Delta habitat, is proposing exactly that. The project would consist of two tunnels, buried 150 feet beneath the heart of the Delta, which would help divert water from the Sacramento River to southern California. In order to proceed, the project planners must apply for permits from federal and state fish and wildlife agencies. The BDCP includes an adaptive management and monitoring program that accounts for reasonably anticipated ‘changed circumstances’ such as flooding, levee failure, drought, vandalism, or wildfire. ‘Unforeseen circumstances’ are those that the BDCP does not expect. These circumstances could affect one or more species, or the habitat, natural community, or geographic area covered in a permit. If the unforeseen circumstance involves ecological degradation resulting directly from the BDCP, the project operators will have to mitigate the situation. However, given how many factors influence the ecosystem, it’s unlikely that it can be proven that any one cause – BDCP included – is primarily at fault for environmental decline. For unforeseen circumstances, the permit holders will have regulatory assurance in the form of the ‘No Surprises’ rule. The rule maintains that once a permit has been issued, the federal government cannot require additional conservation or mitigation measures, or restrictions on resource use, to address unforeseen circumstances. As currently proposed, the BDCP is ultimately not flexible enough to meet the demands of the ever-changing environment in California, where “unforeseen circumstances” are the rule, not the exception. Cape Horn Dam in 1964 (left) and Scott Dam in 2014 (right) - Eel River, California In 1964, "Water over both Cape Horn and Scott Dams was so high that you could barely tell a dam was under the flow." (x) If Governor Pat Brown had been told that extraordinary water shortages would direct water policy conversations only twelve years after he stood looking out over the flooded North Coast, it would have been difficult to fathom. And yet from 1976 to 1977, rainfall in California was the lowest on record, and the resulting drought decimated California industry. The climate, ecosystems, and social perceptions of the Bay-Delta have changed dramatically over the past 50 years, and “no surprises” is not a promise that the BDCP make to Californians.

|

Details

AuthorsFriends staff, interns, and Board members. Archives

November 2018

Categories

|

|

© Friends of the San Francisco Estuary. All rights reserved.

Friends of the San Francisco Estuary is a 501(c)(3) organization Tax ID#: 68-0265026 Web Designer: Mark Bentivegna

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed